Our Newest Tutorials

Gear Reviews & Guides

Discover Conservation Photography

Get Down to Business

Find Your Next Adventure

WHAT DO YOU WANT TO READ TODAY?

Search

POPULAR SEARCHES: Best Cameras | Location Guide | Best Lenses | Wildlife

Ready to level up your awesome?

Start your next learning adventure

52 Week Creativity Kit

A year of weekly bite-sized nature photography concepts and challenges that strengthen your camera skills and provide endless inspiration.

6 Must-Have Shots for a Photo Story

New to photo stories? Start by learning how to create a powerful photo story with the 6 essential images that all photo editors want to publish.

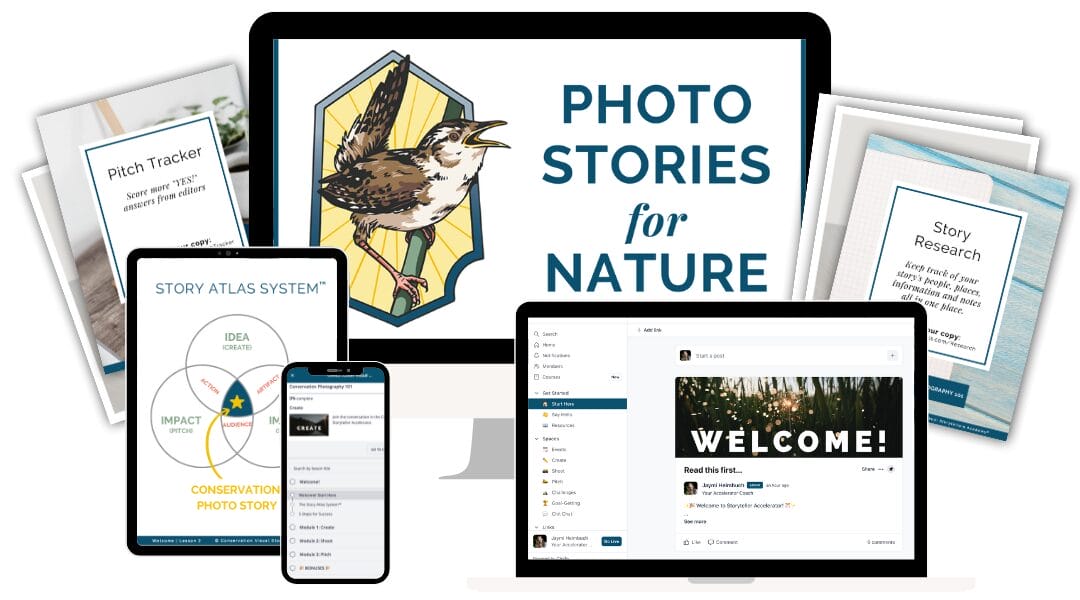

Photo Stories for Nature

Master how to photograph impressive photo stories and effectively share them so they make an impact.

Conservation Filmmaking 101

Master how to craft powerfully moving films that create conservation impact.