Controversy Over Tule Elk Conservation On The Rise As California’s Drought Worsens

The story of the tule elk seems to be perpetually wrapped up with the story of cattle ranchers.

In late 2013, I wrote an article about the surprising story behind the tule elk species. The smallest subspecies of elk, and the only elk endemic to California, the tule elk was nearly erased from the earth forever. It was a cattle rancher who saved the species.

From How a cattle baron saved California’s elk from extinction:

“It came down to one breeding pair of elk, discovered in the tule marshes of Buena Vista Lake in the southern San Joaquin Valley. Huge herds once covered the California landscape, with numbers estimated to be over 500,000. But, like so many species, they suffered at the hands of the Europeans. The elk were hunted for food and hides by Americans arriving to the west coast, especially during the gold rush of 1849.

“By 1873, elk hunting was banned by State Legislature but it was too late. The damage was done and tule elk were thought to be extinct. That is, until that tiny band with its single breeding pair was found in the tule marshes on the land of cattle baron Henry Miller in 1874 by a game warden named A. C. Tibbett. Miller told his ranch hands to keep the elk safe, and it is this action that is credited with sparing the species from disappearing altogether.”

Tule elk is a small subspecies of elk found only in California. They were the dominant ungulate in the area until the arrival of the Spanish settlers.

With Miller’s death, though, the protection ended. The ranch was subdivided, hunting resumed, and the elk population dropped to just 28 individuals. Hope seemed lost until another rancher, Walter Dow, brought a group of tule elk to his own ranch and allowed them to thrive, though he kept the herd capped at 500 individuals.

Eventually, California’s Department of Fish and Game stepped in and, along with more than a decade of work by conservationists, US Congress agreed in 1976 that federal lands would be made available for reserving tule elk, including the San Luis Wildlife Refuge, Concord Naval Weapons Station, Mount Hamilton, Lake Pillsbury, Jawbone Canyon, Point Reyes National Wildlife Refuge, Fort Hunter Liggett Military Reservation, and Camp Roberts.

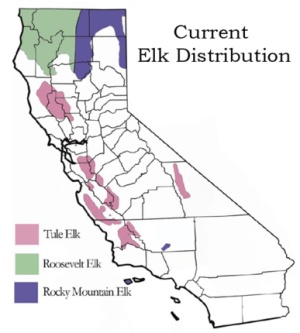

Today, there are 22 populations of tule elk throughout California with numbers estimated at around 4,300 individuals.

It seemed like this was a great story of success when I wrote the article. But doesn’t address the years of controversy and rivalry between cattle ranchers and the newly rebounded elk herds, which flares up during tough times such as now during a record-setting drought.

Numbers are just one indicator of success for the recovery of a species, but not necessarily the most important. Coexistence with a native species is the ultimate success for conservation. Now that California’s drought is nearing historic proportions with no sign of breaking, tensions are reaching a new high as competition for increasingly dry grazing land tightens. The survival of the tule elk species is still dependent on how ranchers react to their presence even when times are tough, and on how the Department of Fish and Game reacts to pressure from ranchers.

In an LA Times article from December 2014, a rancher leasing 800 acres in Wind Wolves Preserve, about 10 miles west of Bakersfield, calls tule elk “sorry varmints” and “trespassers.” When one is a cattle rancher leasing land in a preserve set aside for wild species, one might reconsider exactly who is the trespasser. Still, this is how many ranchers feel and the Department of Fish and Game is quietly bending to their will.

According to the article, “the agency has quietly stopped expanding herds of the species… Instead, the agency’s strategy is to respond to complaints by transplanting ‘excess elk’ from one herd to another.”

As elk become plentiful in an area, to the point of causing grumbling from ranchers, a number of them are transported to another reserve.

This strategy has distinct benefits, both in keeping the peace and in keeping the gene pool as diverse as possible, though some conservationists may feel that the relocations are done for the wrong reasons.

“In 2006, the state relocated dozens of tule elk from the San Francisco Bay Area’s Concord Naval Weapons Station to make way for subdivisions,” states the article. “This year, dozens of ‘excess elk’ were moved from a 750-acre pen in the San Luis National Wildlife Refuge near Merced, Calif., to Wind Wolves in Kern County.”

The Bay Area has its own controversy over tule elk. Commercial dairy farmers leasing land from Point Reyes National Seashore are continually asking park officials to keep elk off land leased for grazing.

The park as a whole is 71,028 acres, and dairy farmers use about 28,000 acres of land in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Point Reyes seashore.

According to an LA Times article, “The park service charges ranchers a grazing fee of just $7 a month for a cow and a calf. That fee on private land in neighboring communities ranges from $16 to $25. The homesteads where some ranch families live are leased to them by the park at less than market rates.”

The ranchers say that the elk threaten the existence of their business, especially after prolonged drought. But ranchers equally threaten the existence of the elk in drought conditions by pushing for limiting where the elk can roam to get enough food and water.

According to Point Reyes Light, “The fate of many tule elk in the Point Reyes National Seashore last year largely hinged on whether or not they were enclosed in a fence. The fenced herd at Tomales Point dropped by 20 percent during 2014, while the two free-ranging herds grew, according to seashore wildlife ecologist Dave Press. The seashore attributes the success of the free-ranging herds to their ability to seek out forage and water at a time of drought.”

There is a twist of irony here. The Park Service recently began to create a ranch management plan after Interior Secretary Ken Salazar made a promise to maintain the ranching and farming heritage along the Point Reyes seashore – but it is a heritage that began during (and partially caused) the near extinction of the tule elk species in the first place.

How can these two things – ranching and the preservation of a species considered incompatible with ranching – coexist?

And coexist they must. Bay Area conservationists are unlikely to allow the tule elk, a native species and a tourist attraction, to plummet back down to former low numbers. The proof is in the public comments:

“The vast majority of the 3,094 public comments on a ranch-management plan support allowing a free-roaming tule elk herd on the peninsula, with 90 percent urging the park to make protection of the native animals a priority,” reported the SF gate in October 2014.

“The public doesn’t want these elk relocated, fenced into an exhibit, shot, sterilized or any of the other absurd proposals from ranchers who enjoy subsidized grazing privileges in our national seashore,” said Jeff Miller, a conservation advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity, who promised a legal and public relations fight if the park decides to fence or relocate the elk. “I think on balance the cattle are eating more grass that’s supposed to be going to wildlife than the other way around.”

Coastal California is one of the rare places where conservationists might just have as much political pull as cattle ranchers. Maybe just enough to keep elk numbers slowly growing. The elk will of course never rise back to their historic population of a half-million individuals, but will the current 4,300 elk at least be allowed to grow over 5,000? Over 10,000? For perspective, California is currently ranked fourth for cattle production with 5,150,000 head in 2015. (More than 50 percent of the total value of U.S. sales of cattle and calves comes from the top 5 states, underscoring California’s pull as a cattle producer. The conservation of elk is up against a significant amount of political clout.)

The 22 herds of tule elk in California are isolated populations. It is difficult for elk to move between the herds because of human development. It is up to the Department of Fish and Wildlife to move elk from place to place to keep the species genetically healthy and to reduce conflict with farmers. But where else can they go? If they are on reserves and yet still facing pressure from cattle ranchers also utilizing those reserves, what next?

A study at the Tomales Point Elk Reserve indicated that the elk are crucial in maintaining the biodiversity of grasslands, preventing them from turning into shrub-dominated ecosystems. They help to maintain biodiversity among both native and exotic flora species, while also reducing the invasive and problematic Holcus Lanatus grass.

Cattle ranching can often be at odds with native species like elk that compete for land (and predators, but that’s a topic for another article). Thankfully, it was a cattle rancher who saved the elk in the first place and who can still in some ways act as an inspiration for others. So too can cattle ranchers with an eye for holistic management.

Bay Nature recently reported on the importance of ranchers and their role in land stewardship: “Sasha Gennet is a senior scientist with the Nature Conservancy of California, which works to assemble and manage large protected landscapes for biodiversity and climate resilience. ‘Managed rangelands are so important for both natural and human communities,’ she says, ‘from the fresh water that flows off them into creeks and reservoirs to the weed-munching services provided by cattle, which helps keep the wildflowers blooming and the native frogs and salamanders breeding. And keeping ranchers in business means that the land doesn’t end up getting paved over.'”

Finding the delicate balance between keeping land safe and protected for wild native species while still also carefully utilizing it for the benefits of humans is difficult and essential. To reach this point, conservationists and ranchers and farmers have to learn how to work together, how to have conversations and not debates.

The preservation of wildlife and jobs is not and can never be an all or nothing approach for either side. Sacrifices and compromises from both sides are part of finding solutions that benefit the entire ecology of an area.

One rancher interviewed for the Bay Nature article is Doniga Markegard of Markegard Family Grass-Fed near the Santa Cruz Mountains, who is walking this very delicate line successfully. Bay Nature writes, “She had a background in nature-based education and permaculture, with experience as a wildlife tracker, when she met her husband, Erik Markegard. He is a sixth-generation rancher raised on a 2,000-acre ranch in San Mateo County owned by musician Neil Young, where he learned the ropes by helping his father manage the ranch. After Doniga and Erik got married, they moved on to a nearby ranch on the San Mateo coast where Erik had been raising his own cattle since 1987. Both Doniga and Erik are keenly attuned to the value of healthy food and healthy landscapes. They guide the grazing of their cows and sheep using movable electric fences to avoid overgrazing and soil erosion, a practice known as holistic management.”

Days Edge Productions created a fantastic video highlighting ranchers who take land stewardship seriously. I watch this and imagine what Henry Miller might say to today’s ranchers who view the native species he helped save from extinction as competition or danger to their businesses. I imagine him and Walter Dow pointing out that they are part of the natural landscape, were here first, are a unique species found nowhere else, and are something to work with rather than against. As stewards of the land, we owe it to them.

(Originally published April 2015)

Resources:

LA Times, December 2014

LA Times, May 2014

CDFW Wildlife Investigations Lab Blog

SFGate

BeefUSA

CattleRange

Point Reyes Light

Bay Nature

Originally published April 2015

[mashshare]